|

Do you have a student in your classroom who can read and write in their home language, but are still learning vocabulary in English? Are you teaching a Core French unit and need a vocabulary list? This is a quick and easy way to translate multiple vocabulary words from English into your target language.

1. Go to your Google Drive and open a Google Sheet. 2. Down the first column, type the vocabulary words you want to translate, one vocabulary word per cell. 3. To translate into French, in the first cell of the second column, type the following: =googletranslate(A1,”en”,”fr") and hit enter. 4. Click on the first cell in the second column, then, with your cursor, grab the blue square at the bottom right of the cell and pull it down the column. This will translate the rest of your column of vocabulary words into French. To translate into a different language than French, simply replace the “fr” with the two-letter code for your target language. If you are translating to a language that uses gendered articles, you may want to add the article in English (for example, “a coat” to get “un manteau”). Some common languages we often need to translate to are: Simplified Chinese: zh-CN Filipino: tl French: fr Hindi: hi Japanese: ja Korean: ko Farsi: fa Portuguese: pt Russian: ru Spanish: es A complete list of two letter language codes can be found here: https://sites.google.com/site/opti365/translate_codes Caveat: this process is using Google Translate as the vehicle for translation, so some errors will be inevitable. Which is true of any translation attempt we make into languages we ourselves don’t speak, barring using a native speaker as an interpreter. One of the challenges of understanding maps is making the jump from the image on the page to the reality of the world. This is especially challenging when it comes to scale, both distance and elevation. When we work on contour mapping, there are always several students in the class who have a hard time picturing how those lines on the map turn into hills, mountains, and valleys.

I decided to make the idea of contour mapping more concrete for them. Materials:

I chose to make up a few batches of play-dough, as I wanted my kids to make individual creations, and that gets expensive on the school’s plasticine stores. Starting with the blue, students roll out the clay to a uniform thickness. I had my students aim for about 1/2 to 3/4 of a cm. The blue is cut out to fill as much of the poster-board square as possible. These are the coastal waters. Another colour is rolled out and the lowest contour of the island is cut out and placed on the blue. Continue rolling out and cutting out the colours to create peaks on the island. After the layers are in place, use a pencil or chopstick to gently angle each layer to that it slopes smoothly from level to level. Students then place the graph paper beside their island and, looking down at the island from the top, draw the contour lines. They then colour their map according to the play-dough colours, adding in compass rose, legend, and title. My students loved the hands-on aspect of this quick little project, and it did a very good job of illustrating the link between elevation and contour lines. Play-Dough Recipe

Mix together in a pot and cook over medium-high heat, stirring constantly, until it coalesces into a single solid glob. (About 2 to 4 minutes.) Turn out onto counter and knead 3-4 times to form into ball. Store in air-tight container. Deepen conversations and thinking with Liberating StructuresOn May 21, Leyton Schnellert will present “Using Liberating Structures in Middle Years Classrooms to Deepen Learning” at the myPITA/BCATML Spring Mini-Conference. Liberating structures are strategies to facilitate conversations, which lead to increasing engagement, depth of sharing, and idea generation among participants.

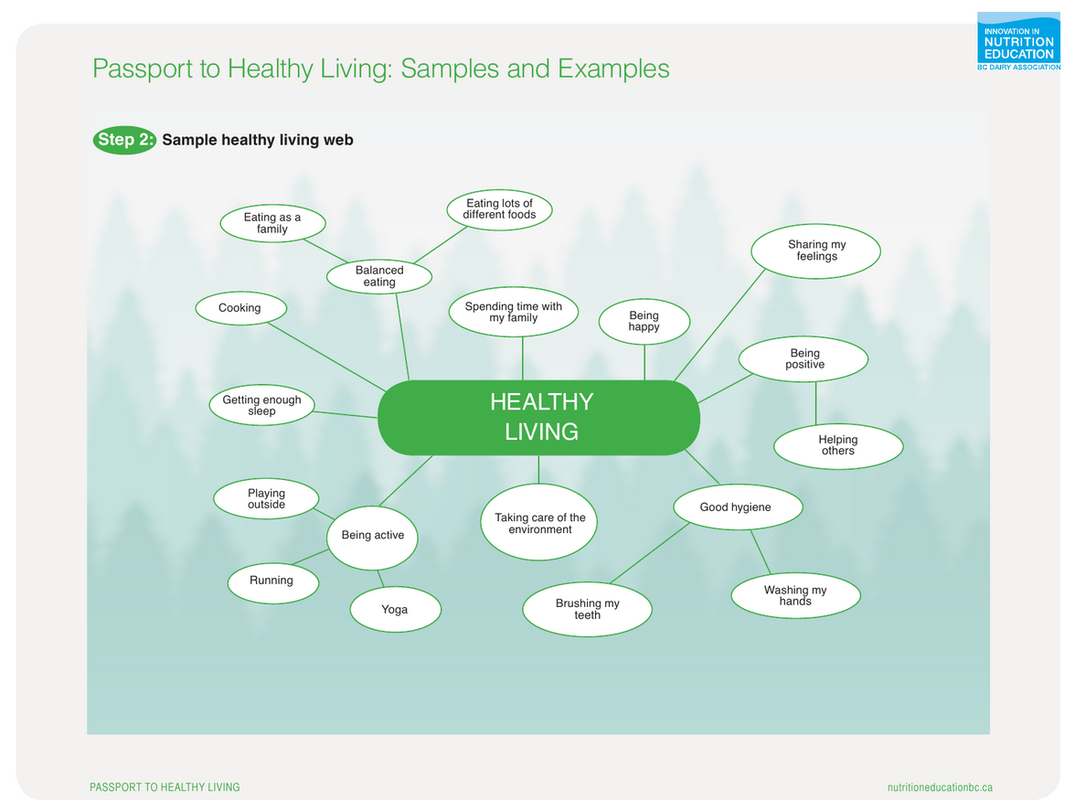

An example of a liberating structure is W3, which is a great debriefing strategy to use after a shared experience, progress check-in, and to generate ways of moving forwards on a repeated or long-term task. In your classroom, it can be an effective way to identify positive group work skills, have students dive in-depth into observations about a character’s actions and how they are portrayed by an author, or to assess the success of an ADST project. The fundamentals of the W3 liberating structure comes down to small groups answering three basic questions: What? In answering the “What?” question, students look carefully at the facts of a situation, describing them as concretely as they can. Prompting questions might be: What happened? What did you notice? What facts or observations stood out? By listing them all out, students work at establishing the verifiable elements of an experience or observed situation. So What? Having established what happened, the next step is to establish the value these observations have? Why is it important? Are there any patterns to see here? Why do we think those events or facts occurred? Are there ways to group these facts together that make sense and help us understand how events unfolded? Now What? The final stage of the W3 liberating structure is to generate future actions. Given the ideas from the So What, what changes can be made to how students address future endeavours in the same vein, or what might be their predictions for future actions or events in a novel, based on past information and characterizations. This is just one of many Liberating Structures, all of which have a variety of potential uses in the classroom to help increase productive conversations and deepen student reflections. Learn more about Liberating Structures by registering for Leyton's session (or another) on May 21 at http://spring-mypita.ourconference.ca. Image: From BC Dairy Passport to Healthy Living resource package. Staying healthy looms large in people's minds right now. Between the very real worries students have around COVID and the mental health concerns surrounding the isolation we've been facing with so many restrictions on our usual behaviours in place, addressing the need to encourage our students to prioritize increased health and well-being is important.

We would encourage teachers to take some time to brainstorm with students regarding how they can help live healthy lives. Just seeing all the things that can (still) be done can help students feel a sense of empowerment over what sometimes feels like an overwhelming situation well outside their ability to control. At our Fall Conference on October 23rd, BC Dairy is running a workshop called Passport to Healthy Living (D06), which provides a cross-curricular unit that challenges students in grades 4-7 to explore healthy living and plan an activity that integrates physical activity, nutrition and environmental awareness. It's a great place to start to take a deeper look at helping your students towards healthy living. Conference registration continues at https://mypita.ourconference.ca/index.php This would have been the 40th anniversary of Terry Fox’s Marathon of Hope, and allowing COVID to disrupt Terry’s legacy seems incredibly wrong, especially when those who are living with cancer are among our most vulnerable. With no assemblies this year, and no mass gatherings, how to run Terry Fox Day at your school will require a little ingenuity!

Here is one way that you can bring the Marathon of Hope to your school: Instead of a mass run on a single day, turn it into an extended event. Each class walks or runs a route (the distance around the outside edge of our field is 300m, for example) daily or every other day and records how far they have run. Those totals are recorded by the class and submitted to your Terry Fox lead, who can either record the total on a map of Canada, or on a simpler chart. A cut-out of Terry running along a distance-marked length of road would be a great visual as well. You don’t need to be completed by the “official” Terry Fox run day… given the late and complex start to the school year, extending your Terry Fox run/donation time by a few weeks makes sense. Can your school make it the 5373 km to Thunder Bay? If your school is smaller, you may want to choose a shorter distance… it’s 3101km from Thunder Bay to Victoria, where the Marathon of Hope was to have ended. If you have a large school, maybe you want to try for the full 8474km distance across Canada. This activity has the advantage of fulfilling DPA requirements, and getting your classes outside into the fresh air! You can also use it to review basic math skills and number sense in the class. For instance, at the Primary level, (our recommendation to our Primary teachers is to round three laps of our field to 1km), counting and keeping track of how many kilometres your class has run can be a great time to practice tens, ones, and grouping/counting by tens. At the older grades, keeping the 300m distance would mean that you can work on adding decimals and multiple of three. If you are having students do as many laps as they can in a given time period and having each student keep track of their own, I’d recommend handing out lap-tokens (I use popsicle sticks, but have also used plastic counters, which can probably be sanitized more easily) as students will tend to lose track of how many laps they have run. Alternately, to simplify your accounting, you can just have students each run 3 or 5 or 10 laps. The Terry Fox Foundation has a theme of “What’s your 40?” for the 40th anniversary. You can check out in-class activity ideas here: https://terryfox.org/schoolrun/whats-your-40/ One idea might be for your Terry Fox lead to create 40km certificates and to post them up near your distance tracking as a class reaches 40km run. For every 40km after that, another certificate could be added (if, like us, you have 23 divisions, choosing a different colour for each subsequent 40 and layering them may be needed for space constraints!) While many fundraising techniques (bake sales, for example) are not an option this year, the Terry Fox Foundation has online donation capability, making it easier for friends and family who are more physically distant to participate. If your school enjoys a robust Terry Fox Day culture, with celebration assemblies and incentives (if you raise $XX, teacher A will do this… if you raise $XXX, teacher B will do this… if we get to $XXXX admin will do this), some of those incentives could be recorded and shared by the teacher in the classroom. This year, given the potential for family incomes to have been affected by COVID, we have chosen to attach the incentives to the number of kilometres run, rather than the money raised… however, we will be promoting fundraising in our school all the same. Good luck to all BC schools as we continue to honour Terry’s legacy and continue his Marathon of Hope. This is going to be one of the strangest starts to the year that BC education has ever faced. There are so many moving parts and as we go into this, so many of us are facing uncertainty and anxiety over what we should be planning for. Looking forwards, we can expect a few things to potentially occur, and hopefully planning for these events will help us feel like we have at least a tiny bit of breathing room.

1. Classroom community is key. Relationships are a huge part of what will make this year function, and it is important that this is where we start, even with the tension we will feel to push into curriculum when our teaching time is so greatly reduced by health and safety protocols or by compressed schedules in the older grades. The relationships will be what allow us to support our students through the changes that may occur over the course of the year. 2. Disruptions and switching between in-class and isolation at home is a distinct possibility. If the local health officer orders a classroom or cohort to isolate, we may have to switch on the fly. Just like we put together our “I’m too sick to plan for a TTOC” dayplans of emergency activities, have two or three days of emergency independent home learning planned and ready to go. If you happen to be able to update it as you go along so that it involves review of material you’ve already covered in class, that’s amazing… or it can be skill building and review of last year’s concepts. It will allow you the time to set up and switch over to your online classroom in a less rushed and panicked manner, since your students have meaningful work to occupy them while you make that shift. 3. Chances are, you may end up stuck at home with mild cold symptoms while you wait for COVID test results. It’s anyone’s guess what the TTOC situation will be like this year. Those “too sick to plan for a TTOC” day plans? You probably want to have two or three days worth of them ready to go. 4. Keep your safety a top priority. There are safety protocols that are required to keep us safe. Many of us feel that they are insufficient, but we need to remain vigilant in making sure that what protocols there are are followed. If your school/district is not following the PHO and WCB’s health and safety protocols, please document it and report it to your health and safety committee and, if that doesn’t garner results, to your Union local. If something feels off to you, contact your local for further support. MyPITA will continue to advocate for reduced classroom density and extra support for teachers and students this year. These games assume that students are playing within their learning cohorts, and that sharing some equipment with minimal handling is permissible (not touching their face during games, washing hands afterwards to minimize the risks involved). They are adapted to allow for lack of physical touching, but many involve periodic movement to within 2m. As with any time you are organizing physical activities for large groups, consider the diversity in your classroom and make sure to pre-teach or adapt for students who would need help fully participating in the activity.

1. California Kickball/Baseball This game can largely be played as normal with some minor alterations to the tagging-out rules. a. Each corner of the diamond is actually two bases, side by side. One is the base for the team at bat (the running base) and that is the one that the runner must tag to be safe, or in passing. The other base is for the fielding team, and that is the base they must tag to tag a player out. b.) The only way to tag out a player is to tag the base. There is no tagging during the run or during a stealing attempt (you may want to remove the option to steal) 2. Zone Soccer (Human Foosball) Set up your playing area in a grid (either drag your heel through the dirt to create the lines, use cones or use skipping ropes). Students must stay in their own square, though they can move around it. This includes keeping their feet within their square… no stealing the ball from another square. That will probably be the hardest part for your competitive players. You can either stagger the players, or simply use full rows of the same team. Depending on the number of students involved, you may choose whether to include goalies. Play will be a little slower, as students try and make good choices on where to pass the ball, but you can increase the pace of play by either giving a time limit for how long people can hold on to the ball before passing, or by adding a second ball to the game. 3. Mini golf with balls or frisbees Set up a series of “holes” using laminated numbers and hula hoops. Students need to complete the whole course while keeping track of their score (a great time to work on tally marks for younger students, and use the range of scores for mode, median, and mean for the older ones!) Break your class up into groups, and have each group start at a different number to begin with, meaning no long wait times or crowding. Balls in question could be kick balls, handballs, or even bean-bags. 4. Fitness circuit Set up a variety of fitness challenges and have students rotate through them. Have students come up with stations that can be included and switch them out from time to time. Consider having stations be timed, so that it is “as many as you can in 2 minutes” rather than “do 30 jumping jacks” as that allows less downtime and means that students who struggle with a skill aren’t still trying to finish the number of repetition while the rest of the group is waiting for them. 5. Captain’s Orders One person is the leader (Captain). They call out different actions for students to do. You can use the ones below, or make up your own. This game can be easily adapted to link to books you are reading (imagine, for instance, how you’d play this game with a Harry Potter theme) or even subject matter (bonus points to the science teacher who makes this game work for cell division). Man Overboard - Everyone drops to a plank position Captain’s Coming - Stand to attention and salute Starboard/Port - Players run to the designated side of the room… (for the non-nautical, when standing on a boat and looking towards the bow, Port is to the left, Starboard to the right) Scrub the Deck - Crouch down and pretend to scrub the deck Swab the Deck - Staying standing, pretend to mop the deck Climb the Rigging - Pretend to climb Find North/East/South/West - Players point in the appropriate cardinal direction… great for if you’re doing cartography, and you can add in the in-betweens as well if your students are ready for it. Polly Want a Cracker - Flap your arms and make parrot noises Teaching is a profession that is an endless time sink. There is always something more we could do: our lessons could be more engaging; our worksheets could be more appealing; we could create more manipulatives for our math lesson; we could give more detailed feedback on those essays we’re marking. If teachers were given three extra hours a day, we could fill them with nothing but planning and still be wishing we had more time.

Teaching is also a profession that draws on your emotional energy. We teach because we care, and caring for so many young people means that instead of having one, or two, or three children we have thirty, or forty, or a hundred. Did Johnny have a lunch today? Was Mohamed able to find a friend to play with at recess? How is Xi Wen doing today with their mother back in China for another 3 months? Did Tina get enough sleep last night? How can I support Ryder’s mum, who has to work night shifts, to help Ryder complete their homework? It is a daily truth for us that our students bring their home lives with them when they come to school. It is equally true that when we as teachers go home, we take our school day worries with us. This can be overwhelming, especially when our homes have their own stresses and as we are navigating the world amid the COVID-19 pandemic. We may have spouses, children, or aging parents. We may have health concerns, home maintenance issues, or budgetary constraints. We may have hobbies we never get enough time for and passions we feel we’re neglecting. And we often have the guilt that no matter what we do it is never enough. Teachers are Super Heroes. We try to do it all, and often we succeed, but sometimes that comes at a very high cost. Compassion fatigue is endemic among teachers and can lead to serious physical and mental health concerns; in fact, approximately 1 in 42 BC public school teachers are on stress-related disability leave. We have to acknowledge that we are human and have respect for our limitations. Sometimes it is vital that we take off that super hero cape, look at what we’re doing, acknowledge a need to conserve our energy and say, “you know what, that’s good enough.” Could I spend another 15 minutes on this hand out and have it be perfect? Yes, but it’s good enough. Is this lesson exactly as I’d like it and covering all the aspects of the new curriculum I want it to? No, but it’s good enough. Did I respond to Rhett’s emotional issue in the way most likely to help them? Maybe not, but I tried my best and that has to be good enough. We cannot be everything to everyone all the time. The good news is, we don’t have to be. We are one adult in the lives of the children coming through our rooms. We are one of many teachers they will interact with, learn from, and connect with. We don’t have to do it all, because there are others to share the load. So if we are in a place where we can’t be our best teacher self, if we only have the energy and emotional capacity to be “good enough”, that is, indeed, good enough. Don't suffer in silence until it is adversely affecting your work or personal life. If you find yourself dreading coming to school and the emotional labour of the day, talk to your district or BCTF wellness contact. (https://www.bctf.ca/wellness/) This blog entry is an article from a MyPITA Newsletter. Some minor edits are included. Science in the Age of Covid Crisis Teaching - A simple experiment linking temperature to solubility.4/8/2020

Before we start: It is important to know that everything in the world is made up of atoms and molecules, which are tiny, tiny pieces of matter, so small that we can’t see them.

Background information: Solutions (and mixtures) diffuse: to spread out in every direction solute: the substance that is going to be dissolved solvent: the thing (in our case the liquid) that the solute is going to be mixed into in order for it to dissolve dissolve: to mix a substance (solute) with a liquid (solvent) so that the molecules of the substance diffuse through-out the liquid A mixture is when you combine (mix!) two or more things together. The type of mixture we’re looking at this week is called a solution. A solution is a mixture where all the bits of the two (or more) things we’re mixing together are so thoroughly combined (mixed) that you can’t easily separate them any more. Today, we will be looking at dissolving honey into water. When we are working with creating this solution, we combine together the solute (the honey) and the solvent (water). Our question: How does Temperature Affect Dissolving Rate? We are going to test what happens when we try and dissolve honey in three temperatures of water: hot, lukewarm, and cold. This will take some set up, and will require a little help from an adult. You will need: - three clear glasses or glass jars, and one more for chilling the cold water - some tape or scraps of paper for labeling your experiment - measuring cups and measuring spoons - a way to boil water - 3 clean spoons - 6 teaspoons of honey (if you don’t have honey, you can use golden or corn syrup... if you don’t have those you could use granulated sugar) - 6 tablespoons of lemon or lime juice Read through all the instructions. After you have read through all the instructions, think about what you know or what you have seen in the past with liquids, temperature, and mixing things together. On a piece of paper, record your HYPOTHESIS (a hypothesis is a guess where you record what you think will happen and why). Your hypothesis might look like this: The honey will dissolve fastest in __(hot/cold/lukewarm water)___ or The warmer the water, the _(faster/slower)_ the honey will dissolve. Instructions 1.) ONE HOUR BEFORE - fill a glass with one cup of water and put it in the fridge to get really cold 2.) MEASURE 2 tsp of honey (the solute) into each clear glass/glass jar. 3.) LABEL the glasses with the tape/scraps of paper - “boiling”, “room temperature”, “cold” 4.) PREPARE the solvents (the water). Boil some water, get the container of cold water from the fridge, and run the kitchen tap until you get the water to a temperature that is lukewarm/tepid (this means that it isn’t warm but isn’t cold either). 5.) POUR one cup of each temperature of solvent (water) into the glasses containing the solutes. (Get your adult to help you measure and pour the boiling water) DO NOT STIR (yet). 6.) OBSERVE the solutions. Which solvent dissolves the honey the fastest? Next? Last? You can test how well the solvent has dissolved the honey by using a (clean! don’t double dip, because we’re going to use the solutions for something else in a minute) spoon and getting a little bit of the solution out to taste it. 7.) STIR the solutions. How does that affect your experiment? 8.) RECORD your observations and check your hypothesis. Were you correct? Report Out In Science, it’s important that we report out our findings. You will be handing in your findings to Mrs. Slack. She would like the following: 1.) Tell me what your hypothesis was. 2.) Tell me what you observed after you poured your solvents in the jar. What happened after you stirred the solutions? 3.) Why do you think the different temperatures changed how the honey dissolved? Finally... Usually, there’s an important rule in Science and it goes like this: Don’t Eat the Science. However, this is a special science experiment that is designed for you to be able to consume it. Add 2 tablespoons of lemon or lime juice to each glass. Stir, add ice if you want to get it nice and cold, and enjoy!  Recently, I was reading through an article on using Electronic Portfolios and my mind kept coming back to student self assessment. There are several elements of self-assessment that I have been turning over in my mind in the past few years, especially as we move more fully into the new curriculum. 1. Student self-assessment tends to be accurate. In my experience, this is true. In fact, I’d argue that students are usually harder on themselves, when it comes to assessing their ability levels and performance, than teachers are. This, however, relies upon the teacher having provided clear criteria for what the learning objectives are and what success and mastery look like. If I was to ask students to grade themselves with letter grades, the results would be all over the place because letter grades have little to no real attachment to the reality of learning. Students are generally pretty accurate when given a rubric, however. The most interesting to me are those where there is a complete, serious mismatch between the student’s assessment of their ability level and that of the instructor. In almost every case, those have been red flags for me that the child involved should be seeing the school counsellor. In general, it has been either a method to protect a child’s fragile sense of self/adequacy (when they seriously overestimate their ability level) or an indication of depression, trauma, or severe lack of confidence (when they seriously underestimate their ability level). 2. Self-assessment leads to metacognition regarding the learning process. This is one of the reasons I love having students work with me to create a rubric. It is a long process, and one where we can push into what learning actually means and what it looks like, beyond performance/hoop jumping. We can also discuss using rubrics as a means to push your ability levels. What I find interesting, however, is how much motivation plays a role here. When given a rubric, there are often students who, even when the jump from minimally meeting to fully meeting takes only a minimal amount of effort, will produce at the “minimal” level. I’m really intrigued, lately, by the rubric format that my post-bacc diploma professor Kevin put forwards: This model doesn’t give examples of how elements of the criteria might exceed or not yet meet the expectations of the assignment. Instead, it is up to the student, if the work doesn’t fall into the Meeting Expectations column, to indicate how it goes beyond, or falls short, of the assignment criteria. It has students putting in the effort to examine their own work and decide how they can expand it, or where they need support to be successful.

This will require explicit teaching of vocabulary to our ELL students, however, as they will need practice in being able to articulate how things are expanding or developing. So will all students, however, as this is a new form of assessment for them, and will require a fair amount of whole-class and partner practice before they can manage it accurately themselves. I'm looking forward to trying this out with my class. Jennie Slack is a grade 4/5 teacher at Chaffey-Burke Elementary School in Burnaby, and is president of MyPITA. |

AuthorThis blog will feature Intermediate and Middle Years teachers who are passionate about their teaching and love to share! Archives

August 2021

Categories |

myPITA is a Provincial Specialist Association (PSA) of the BC Teachers' Federation (BCTF)

© 2023 Provincial Intermediate and Middle Years Teachers' Association

© 2023 Provincial Intermediate and Middle Years Teachers' Association

RSS Feed

RSS Feed